The Bicycle Club

by Martin Golan

When my parents retired to Florida back in the ‘70s, my father fulfilled a lifelong dream: he learned to ride a bicycle. It thrilled him, being of a generation for whom bicycles were a luxury, the province of uptown rich kids. With a few other men from the condo, he formed a “bicycle club.” Every morning at eight they’d gather at the clubhouse and set off on their brand-new bikes over the flat, Florida landscape, unfurling like a series of flags along the dirt roads that wound through empty fields and brooding palms.

At its height, the club numbered nearly 50.

When I’d fly down to visit, I’d ride with “the men,” as my mother called them (women weren’t officially banned, but stayed away, content, or so it seemed, to sleep late, tidy up, and plan lunch). I’d mount a borrowed bike and pedal off, into a magical, Zen-like world.

We’d ride for an hour, then have breakfast, always fresh grapefruit brought by Leon, the nominal leader. Leon was a creature of his generation: a gruff yet good-natured guy who expressed affection with physical hostility, punching you on the shoulder so hard it hurt to say how much he liked you.

Leon would dispense grapefruits by hurling them at you, throwing pretty hard, often faking high and throwing underhanded. You’d catch it with a palm-stinging slap, and rip it open with your fingernails, juice running down your wrists.

It never occurred to anyone to bring a knife, or a napkin (as opposed to my mother, who would have sliced it open for me on a plate; on my visits, she waited on me hand and foot, which endlessly amused my wife).

The grapefruit, fresh off a backyard tree, had a wondrous taste: sugary yet tart, deliciously bitter and sweet at the same time. It was acceptable to spit; slurping was encouraged; chomping aloud was de rigueur.

Dessert was a shared coconut hacked open with a screwdriver.

But that wasn’t the magic. It was this:

The men had all come of age in the Depression, fought in World War II, and had anachronistic professions like typesetter and furrier and haberdasher. Long retired, career vicissitudes were a thing of the past, the kids long out of the house. Relationship issues, if these silent men ever had any, were history, too.

All that mattered was their health and, being men–especially men of that generation–they didn’t speak much of that.

I’d visit amid a job crisis, or when a kid wasn’t sleeping through the night, or when I was struggling to publish a novel.

Then I’d ride with the men.

Pedaling through the endless Florida summer, watching a bag of backyard grapefruits bob in a plastic Publix bag on Leon’s handlebars, it was impossible not to know that in a few short years, everything I was torturing myself over would be a footnote on my life, a minor, half-forgotten detail.

All that mattered was my health, and I still had the arrogance of youth, where this gift was taken for granted.

Years passed and the men, who rarely spoke of personal matters, proved this point. Old age–time, by a different name–was catching up. One by one they dropped out, too ill or infirm to ride every day.

Leon faded into Alzheimer’s and had to stay back. Others followed with one thing or another. Everywhere I heard the same pathetic album of death’s greatest hits, the same cancers, heart attacks, and strokes, perhaps an organ one never thought about rising with metastatic fury to take down an entire body, along with its lifetime of memories.

The bicycle club dwindled to a few. Meanwhile, without us noticing, the dirt roads were paved and became construction sites. And my father?

It’s something that, were I writing fiction, I wouldn’t dare it. But it happened; it’s true.

At 87, he still rode every day. Then, one cloudless January morning, my father wheeled out his beloved bike and told my mother, “I’m riding over to the clubhouse to schmooze with the men.” At the corner, a Lincoln Continental driven by an 85-year-old neighbor crashed into him, slamming him to the pavement. Even with a helmet, his 87-year-old body couldn’t handle the trauma, and he slipped into a coma and died three weeks later. In a few days he would have been married to my mother for 60 years. We had a party planned.

I still go down to Florida to visit my mother who, at 93, still waits on me hand and foot (and it still amuses my wife). But the bicycle club doesn’t ride anymore. The dirt roads we took are all paved, cluttered with strip malls and condos. And I’ll never again eat homegrown grapefruit with my fingers in a public park, thrown hard at me when I least expect, reminding me to savor both the bitter and the sweet.

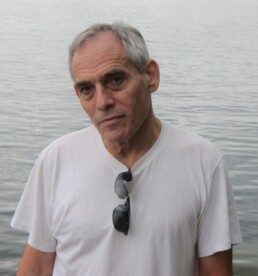

Martin Golan’s newest novel, One Night With Lilith, about a man convinced his wife is the Lilith of biblical legend, has been called “a fascinating feat of storytelling.” He followed it with a well-received book of poetry, A Note of Consolation for Lucia Joyce. His fiction, poetry, and essays have appeared in many journals, including Pedestal, Poet Lore, and Blue Fifth Review, where a poem was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Learn more at www.martingolan.com